What are Fugitive Data Portraits?

“Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and the authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.”

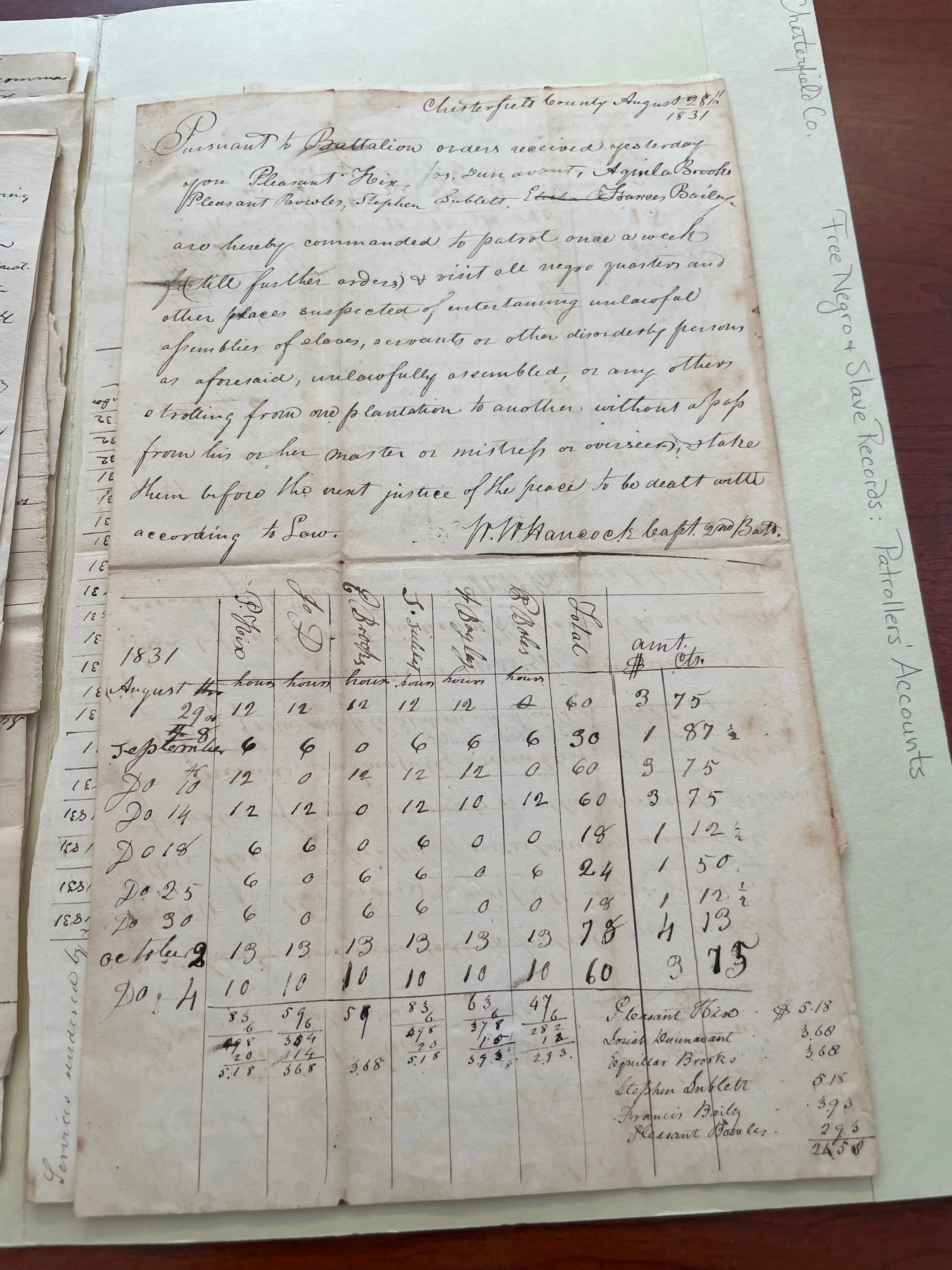

A Note on Archives

I hadn’t thought of myself as much of a historian when I stumbled upon the Library of Virginia’s digitized collection of “Runaway and Escaped Slaves Records”3. But this collection planted the seeds for Fugitive Data Portraits: Self-Emancipation in Virginia (FDP), a history project that aims to provide a glimpse into the lives of some of Virginia’s earliest freedom fighters.

Freeing oneself, or stealing oneself, from slavery was an act that agitated the social and economic fabric of American society during the colonial and antebellum era, contributing to an almost complete unraveling in the wake of the Civil War. An act that for many meant fleeing with family or reconnecting with those already on the other side of bondage, but for most meant leaving loved ones behind without so much as a clue or word of their future whereabouts. An act that led some to a taste of freedom, but others to physical mutilation, permanent disfigurement, or death. FDP reflects on and uplifts “what can be known” of the courageous souls who threw a wrench in the machinery of slavery in Virginia by daring to escape.

This work is subject to the same challenge of grappling with “who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor” that Hartman speaks of. Did Virginia’s Commissioners of revenue record the names of the thousands of enslaved people who escaped during the Civil War because they viewed them as historical actors or stolen property?4 In the essay Contraband of War, FDP begins excavating these names from property records and mentioning them in the same breath as their fellow Black freedom fighters and revolutionaries. Notes on a Criminal Conspiracy honors the efforts of William Still, who documented the testimonies of nearly a thousand fugitives who journeyed through the Pennsylvania Underground Railroad station. Still understood the heroic feat of these escapees, their contribution to the Black liberation movement, and the importance of documenting their stories, noting after the Civil War that “this newly emancipated people will need all the knowledge of their past condition which they can get.”5

FDP brings together personal narratives, interviews, and oral histories of self-emancipation to provide context and a counter-narrative to county and financial records that primarily exist to document property loss, not rebel activity. These archives help shed light on the identities of these brave individuals and collectives. What we can learn about these revolutionaries through these sources is only overshadowed by what we can’t know because of the historical artifacts that no longer or never existed.

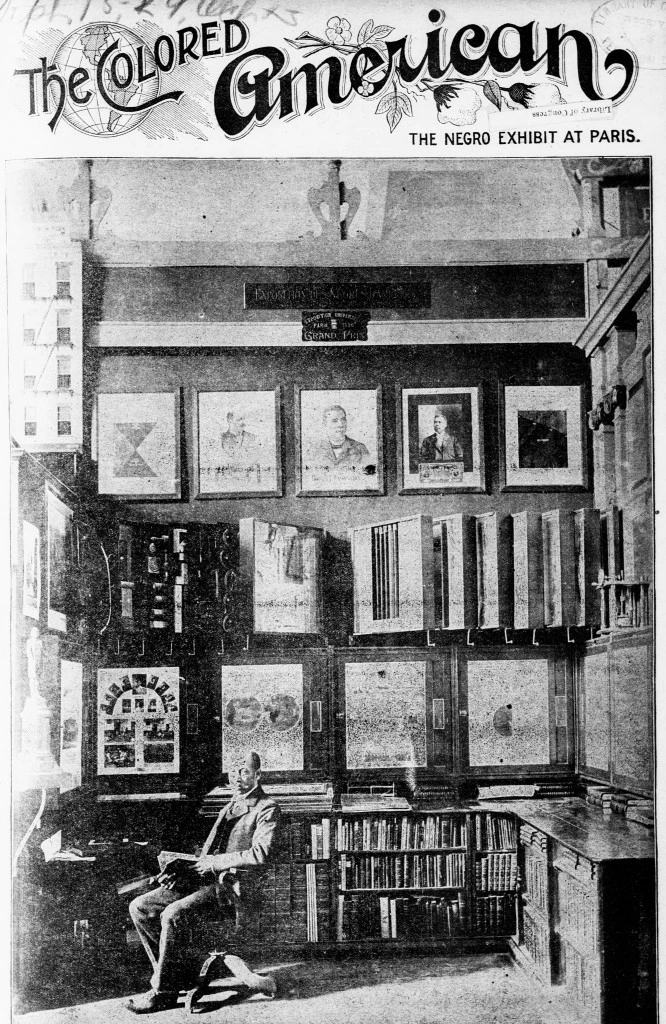

Data Portraits

FDP is also a data project that uses computational methods to illuminate trends and patterns in collective fugitive activity. As a software engineer, data scientist, and linguist, I’ve come to appreciate the power of using language and data together to tell dynamic and multidimensional stories. I find inspiration in the works of those like sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois, who at the turn of the twentieth century was experimenting with designing data visualizations (infographics, graphs, charts, etc.) to communicate the progress of Blacks in America in the years following Emancipation. With contributions from students and faculty at the Tuskegee Institute, Howard University, the Hampton Institute, and other black colleges and industrial schools, he debuted his findings at the 1900 Paris Exposition with his exhibition “The American Negro in Paris”.7 FDP leans into these methods by pairing quantitative archival research with historical narratives to contextualize and breathe new life into stories that are often footnotes in, or altogether omitted from the historical record.

A data portrait is the use of data, computational methods, and visuals alongside contemporary narratives to provide a micro and macro view of historical events. In the case of FDP, the primary sources that detail specific acts of self-emancipation contextualize and frame the experiences of the thousands of escapees whose stories are not documented in the archive. Each data visualization in this series offers visitors an opportunity to engage with Virginia’s historical record through the lenses of time, place, age, sex, and other recorded information.

For an overview of the data processing and prototyping that enables the data visualizations included on this website, refer to the project’s methodology section.

Acknowledgements

This project was developed with support from the Virginia Humanities Public Humanities Fellowship and a residency at the Library of Virginia (LVA). LVA staff, namely John Deal and Lydia Neuroth, have been tremendous collaborators in helping me tap into my inner historian and archivist. I’d also like to share my gratitude to the Richard A. Tucker Library and staff in Norfolk, VA, where I’ve spent many afternoons writing the code and essays for FDP.

Tev'n Powers

Project Director

Fugitive Data Portraits sits at the intersection of my curiosities as a software engineer, computational linguist, and archival researcher. My goal was to share this project as a representation of how I've come to learn about these heroes—through archives and through data. I hope it is of some value or utility to researchers, genealogists, and anyone with an interest in these Black liberation stories.

Contact me or join my newsletter to stay up to date on this project and others.

Press

Citations

1. Hartman, S. V. (2019). Wayward lives, beautiful experiments: intimate histories of social upheaval. First edition. W.W. Norton & Company. https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393357622

2. Chesterfield County (Va.) Free Negro and Slave Records, 1760-1862. Local government records collection, Chesterfield County Court Records. The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia 23219.

3. “Runaway and Escaped Slaves Records, 1794, 1806-1863,” Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

4. Virginia. Acts Passed At a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Passed 1862 (Called) - 1863 (Adjourned).

5. Still, William. (1879) The underground railroad. A record of facts, authentic narratives, letters &c., narrating the hardships, hair-breadth escapes and death struggles of the slaves in their efforts for freedom. [Philadelphia, Pa., Cincinnati, Ohio etc. People's publishing company] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/31024984/.

6. The Colored American. (Washington, D.C.), 03 Nov. 1900. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

7. Battle-Baptiste, W., & Russert, B. (2018). W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America. Princeton Architectural Press. https://papress.com/products/w-e-b-du-boiss-data-portraits-visualizing-black-america